The Story of Princeton University Science Olympiad

December 25, 2018

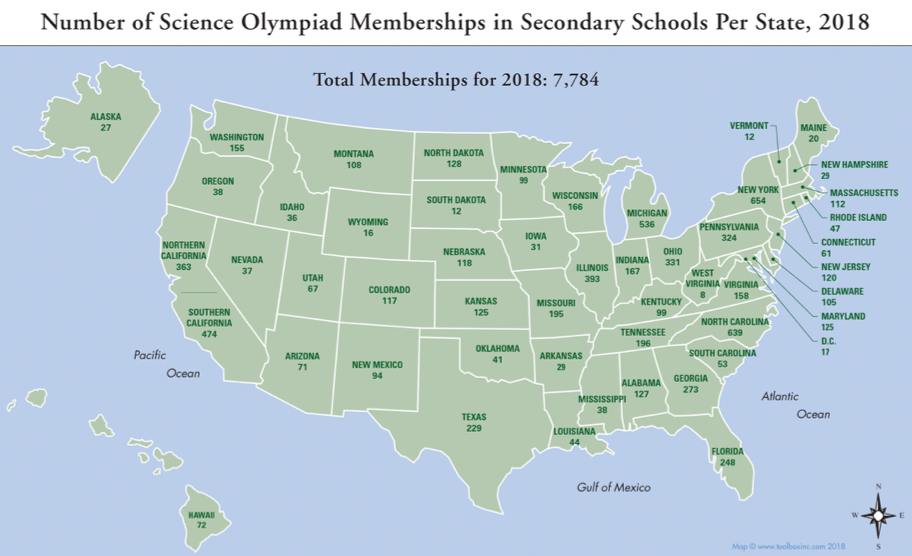

Science Olympiad is a team-based STEM competition that approximately 8,000 middle school and high school teams compete in nationwide. Science Olympiad was a major part of my life from 7th to 12th grade, and an experience that I am very grateful to have had. In fall 2016 (my sophomore year), I cofounded the Princeton University Science Olympiad invitational tournament with Edison Lee. Co-founding this tournament and scaling it up to become one of Princeton’s largest student-run organizations, has been among the most difficult yet rewarding endeavors I have undertaken. I hope to share part of that story with you today.

Background

Competition Format

All Science Olympiad tournaments run the same 23 competition events which rotate on a yearly basis. Events range from pencil and paper tests, to laboratory-based practicals, to engineering events in which students build devices beforehand, which are then evaluated on competition day. All tournaments follow a standard set of rules which dictate exam content areas, specifications for engineering devices, and other subtleties for each event. But, every competition experience is still highly unique because tests are (generally) not reused between tournaments, and organizers have flexibility in deciding how to run the events.

Types of Tournaments

There are three official types of Science Olympiad tournaments: regionals, states, and nationals. Teams that place in the top $x\%$ (varies) for each region advance to their respective state competition, and depending on a state’s total membership, either the top team or top two teams then advances to nationals — the final competition of each school year.

Invitational tournaments (“invitationals”) are sanctioned tournaments that don’t impact bids for states and nationals, but many teams participate in throughout the year, to gain experience for official elimination tournaments. Despite the connotation of exclusivity, invitationals are usually open to any team that is able to register in time, and this is certainly the case at Princeton.

Problem and Motivation

Regional tournaments, and even some State tournaments tend not to be well-run due to three main reasons:

Lack of funding and/or proper venue space

Lack of experienced organizers who have competed in Science Olympiad and know what makes a “good” tournament

Insufficient volunteer manpower

Any combination of these leads to the following problems, which heavily detract from the competition experience:

Not running all 23 competition events

Exams that are too easy, copied verbatim from online sources, or even completely off-topic

Inconsistent application of or misinterpretation of the rules, which confers unfair advantages to certain teams

Non-transparent and/or even incorrect scoring

Low quality tournaments are disappointing and demotivating to students who have spent a lot of time preparing, and generally unconducive for encouraging students to pursue STEM outside of the classroom. I competed for a top New Jersey school district from 7th grade to 12th grade, and experienced the same problems at every regional and state tournament, year after year. These tournaments left much to be desired.

On the other hand, invitational tournaments were (for the most part) free of the above problems, and constituted most of my favorite experiences in Science Olympiad. When I was in high school, the invitational tournament scene was in its infancy. There were a few nearby invitationals organized by particularly motivated high school coaches in Pennsylvania and New York, and none run by universities. New Jersey had no invitational tournaments until I hosted the first at my high school during senior year.

While invitational tournaments were of higher quality and more enjoyable than regional and state tournaments, they still suffered from two major problems: 1) teams were required to pay a hefty registration fee, and 2) coaches from attending teams were required to help run events. Running a good event requires a significant amount of dedication, and attending invitationals in itself costs money. These two requirements presented major barriers preventing inexperienced teams from participating in invitational tournaments. Accessibility of quality invitational tournaments is especially important, because only a select few teams are able to attend States and Nationals. Thus, the only opportunity for most teams to be appropriately challenged and meet teams from other states, is through invitational tournaments. I wanted to create a quality tournament with minimal barriers to attendance, even for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Science Olympiad alumni with similar aspirations at Cornell and MIT founded the first two college-run invitationals in the nation during my senior year of high school (winter 2015). Their efforts encouraged me to follow through with my aspirations after being accepted to Princeton University. I spent freshman year gaining leadership experience through clubs, learning about administrative bodies and regulations, and supervising events at Science Olympiad tournaments such as MIT and NJ States.

The MVP

We defined the following objectives for a successful first year:

Run all 23 events, and ensure that all events are run by experienced Princeton students (zero involvement from competing teams)

Subject every test to a multi-stage revision process

Write tests that are challenging, encourage problem solving over memorization, inspire curiosity, and serve as good review material after the competition

Administer the rules precisely and consistently

Host teams from multiple states, ranging from complete newbies to top national teams

Make all tests and answer keys freely available after competition

No registration fee

2016–2017: The First Year

Eddie and I began preparations during summer 2016, however, we were blocked from making meaningful progress until late October due to bureaucratic overhead and opposition from administration. Liaising with academic departments, booking rooms, and recruiting fellow organizers was prohibited until we obtained recognition as an official campus group. The process for that involved a written application, two rounds of interviews, and an additional meeting with specific university administrators who were particularly wary of high schoolers being on campus. Thus, we had a relatively late start, and needed to release the tournament date before teams finalized their competition schedules.

Determining the date for any event usually requires assurance that all necessary facilities are available and booked, but in our case, we had no such assurances. University administration required that we hold the tournament when class was not in session, in order to “minimize disruption to campus life”. Due to Princeton’s academic calendar in which fall finals occur in January, this limited our possible dates to two weekends; the weekend immediately after finals, and the weekend immediately before the start of the spring semester.

We opted for the latter choice, but because students are on break during that time, we were unsure both of whether all needed facilities would be open (especially wet labs), and whether we would have enough volunteers. Each team is usually given its own home room, and every event is run in at least one room, with some events (such as this and this) requiring large open spaces. We thus needed to book over 60 rooms, which is difficult on a small campus like Princeton’s. Nevertheless, we had to take a huge risk and announce the tournament date before knowing whether the tournament could actually happen, because it would have been too late otherwise to advertise the tournament and organize it.

Certain things were much easier than expected, while others were much harder. Recruiting organizing team members, event supervisors, and volunteers was surprisingly easy even though the tournament was to happen during break. While some volunteers flaked last second and needed to be replaced, we received a steady stream of interest, and mustered a final total of 121 student volunteers from 24 academic departments. In retrospect, this should not have been surprising since Princeton has a large number of Science Olympiad alumni.

Finding appropriate spaces to host events, and obtaining permission to run lab-based events was far more difficult than anticipated. Our tournament in its first year was already slated to become one of campus’ largest events (36 teams = 540 high school students). Thus, administrators from each department wanted proof that we could successfully run the tournament, even though we had no preceding reputation nor opportunity to prove ourselves. In other words, we had a chicken and egg situation. As a result, even booking rooms for paper tests was difficult.

A relationship we developed with the university’s Environmental Health and Safety division proved critical to helping us overcome administrative bias. With their support, and the eventual support of the School of Engineering, we were able to book all spaces needed except an auditorium for awards and the gym for building events. We improvised by utilizing large lecture halls and conference rooms respectively. Princeton’s largest lecture hall holds only 450 students, and so even in the first year, we experienced overflow during awards. The following year, we were able to book the university chapel for awards, which is the largest venue on campus and holds 1,200 students. EHS’ support was particularly important for securing lab space and permission to handle chemicals. They supervised lab events on the day of the tournament and aided in waste disposal, which pacified administration.

We were able to achieve all but one goal (no registration fee) in our first year, due to difficulties securing funding. 36 teams (540 students) from 4 states attended the tournament. An organizing team of 8 undergraduate students, assisted by 121 volunteers from 24 academic departments on the day of, ran the tournament. We were featured in this article.

The first year’s challenges were mostly about figuring out what precedents to set, overcoming administrative and financial difficulties to successfully build infrastructure from scratch, and building a good reputation. Accomplishing these set the framework for our second year, in which we focused on scaling up and holding another successful tournament.

2017–2018: The Second Year

Despite wanting to direct a second year, Eddie and I decided it would be best to impose a one year limit on director terms, in order to ensure the tournament’s future viability and introduce new blood to the organizing team. I thus took on a mentorship role, and aided in a few key developments.

Our success in the first year paid big dividends, as we suddenly had a positive reputation to speak of. Over the summer, I managed to figure out the archaic system that is Princeton IT. In our first year, we relied on a free domain given to each university NetID, which gave us an url of princeton.edu/~scioly (now deprecated). As you can tell, the tilde looks undesirable, and despite our best efforts, our request to remove the tilde was denied on the grounds that we were only a student group $…$ Over the summer, I figured out how to obtain a cPanel LAMP server through department sponsorship, which landed us the fashionable url scioly.princeton.edu. (For anyone interested, here are the instructions). It was again EHS whose good will helped us get past administrative barriers.

Our success in the first year paid dividends in other ways as well. Administrators were less skeptical, more friendly, and thus organizing the tournament became a bit easier. We were able to hold the tournament when classes were in session, and book rooms well in advance. We raised enough money to become the first tournament to completely waive registration fees — something I remain proud of. We were able to host event supervisors from other universities for events that Princeton students were not as experienced in. We were able to book the university chapel, which is the nicest venue on campus, for awards (see picture below). However, we were still unable to obtain the gym and needed to use lecture halls and other rooms to hold building events. Molecular biology was unable to lend us the labs, and so we borrowed lab space from the Geosciences department. The lab space was not fully equipped, and so we needed to bring in gas for Bunsen burners and waste disposal bins.

We hosted 48 teams from 9 states, and had 128 volunteers from 25 academic departments on the day of. Our organizing team grew from 8 members to 19, and we received a feature article on the University home page. While we faced logistical challenges in the second year as well, the most difficult challenges revolved around people management. It was difficult to foster a close-knit environment with such a large team, communicate clear expectations, and effectively pass down knowledge. Figuring out an effective system for documentation and leadership transfer is something that we as an organization continue to improve upon.

Miscellaneous

Lessons Learned:

- Relationships are important

We were able to overcome many challenges by building personal relationships with those in power, and using people who already knew about our work and trusted us as points of reference

- Don’t take no for an answer immediately

We were often turned down initially by administration for requests that we eventually gained approval for. It is important to be persistent and fully understand the other party, rather than assume that they are on the same page. The reasons for our initial rejections ranged from legitimate concerns, to $…$ lacking time/motivation to ask for clarification and instead acting on wrong assumptions, conflating other student groups’ activities, and accidentally clicking the wrong button.

- Leadership is about the right balance between communicating vision and giving autonomy

Organizing members need to understand the overall vision and intentions for tournament logistics. However, they also need enough autonomy to feel in full control of their work, and thus take initiative. It can be difficult to strike the right balance especially when there is time pressure to get things done.

Noteworthy Incidents

Transporting 200 pounds of plywood and other construction material in 20 degree weather, from central campus to a dorm and back to a machine shop (best workout ever)

Stapling 10,000 pages of tests the day before, solo. Exhausting my own and two of my friend’s semester color printing quota to save money

Pushing a cart with > $5,000 worth of lab equipment outdoors between laboratories

Getting temporarily banned by campus center postal services for shipping too many packages (read: trophies, medals, t-shirts, supplies) to my mailbox

Philosophy on Test Writing

Tests should be hard enough to challenge the very top teams, but have enough questions on the easier spectrum for less experienced teams to comfortably do

Scores should be normally distributed with wide spread. It is not enough to ensure that a high score is difficult to achieve

Questions should be easy to grade quickly and consistently, as not all volunteers have the same expertise as the event supervisor

Questions should encourage unconventional thinking and problem solving

Policy on Test Release

Test trading is a recent phenomenon in which competing teams trade tests from invitationals they’ve attended, in order to gain access to tests from invitationals they haven’t attended, which serves as good practice material. The phenomenon exists because invitational tournaments typically don’t release tests, and thus tests become somewhat of a limited commodity.

We decided early on to go against convention, and fully release our tests and answer keys immediately after the tournament. We believe that doing so benefits the Science Olympiad community most as a whole, especially for those who want to but are unable to attend competitive invitational tournaments such as our own. Furthermore, the value of attending a tournament is much greater than that of obtaining a stash of test papers. Competing teams seem to agree; we have no experienced any lack of interest as a result of our test release policy.

Vision for the Future

Princeton University Science Olympiad is a non-profit student organization dedicated to inspiring creative problem solving, STEM literacy, and love for learning through its annual high school invitational tournament. We want teams of all backgrounds to be able to experience an innovative, challenging, yet fun Science Olympiad experience that motivates students to learn outside the classroom.

While we have waived registration fees, travel cost is still a barrier to some teams attending tournaments. We hope to be able to provide need-based travel stipends in the future. We also hope to host middle school division in the future, but are currently constrained by campus space. When Princeton finishes its campus renovations in a few years, we may be able to expand our tournament further, or even host Nationals. Finally, we hope to expand our presence in the Science Olympiad community by mentoring local teams and being more involved with the Regional and State tournament.

I look forward to enjoying our third annual tournament, coming up on Saturday February 9, 2019.